Reflections on Inventing a Genre, a Movement, and a Musical Language

Back in 2005, I began using the term Ancestral Soul to make sense of a sound I was building that didn’t sit comfortably anywhere else.

The music came first. The name followed once it was clear the work was here to stay.

The turning point came in 2006, after witnessing a live performance by Osunlade at Stereo Sushi in Antwerp. That night, something happened to me that had never happened before.

For the first time in my life, I cried while listening to music. While dancing. Not out of sadness, but because I recognized myself in the sound.

What I heard was pure ancestry, rhythm, and spirit carried into a contemporary electronic space without compromise. It felt alive, physical, and undeniable.

I went home that night and started making music immediately.

Within a week or so, I sent the project to Osunlade by email. I told him the music was directly inspired by his set and that being on Yoruba Records would be a dream. He replied within an hour. He said he loved it, that it was Yoruba Records material, and that I should consider myself part of the label. A dream came true.

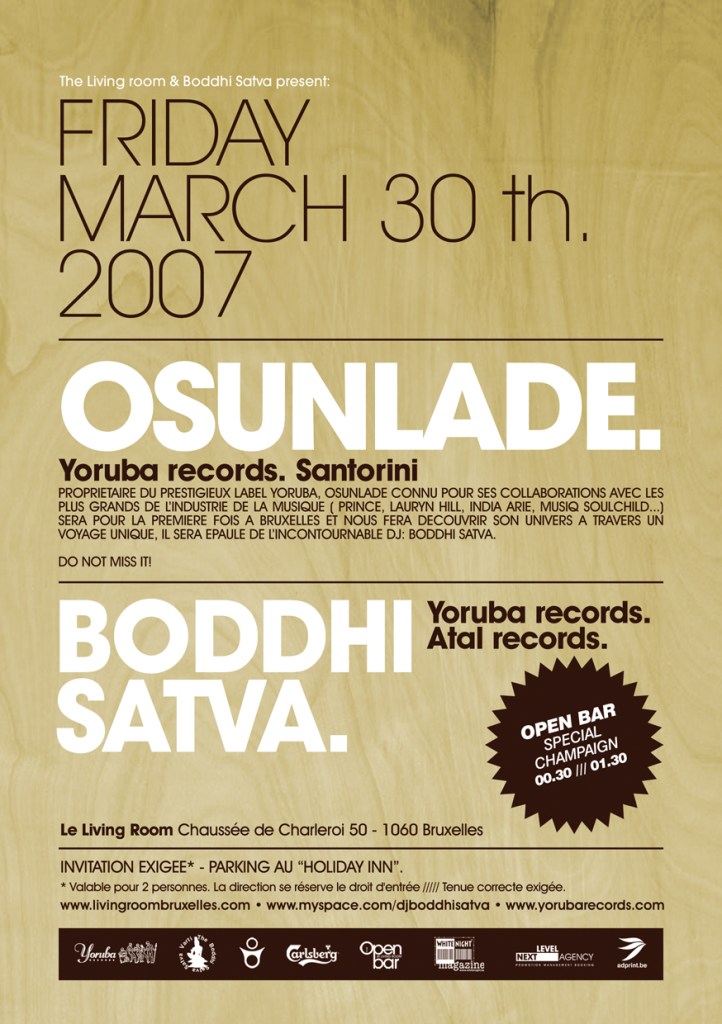

Out of that state came Bria’s Offering, a track that would become one of the most important pieces of my early years. About a year later, I was playing alongside him at the legendary Living Room in Brussels, closing a circle I hadn’t even known I was drawing.

That moment didn’t just create Ancestral Soul.

It made it undeniable.

BEFORE THE LANGUAGE

I was introduced to electronic music in the 1990s through my older brothers, but it was my father’s youngest brother, Patrice, who truly sealed it for me. In the summer of 1999, he introduced me to Kevin Yost’s One Starry Night album. That record landed deeply.

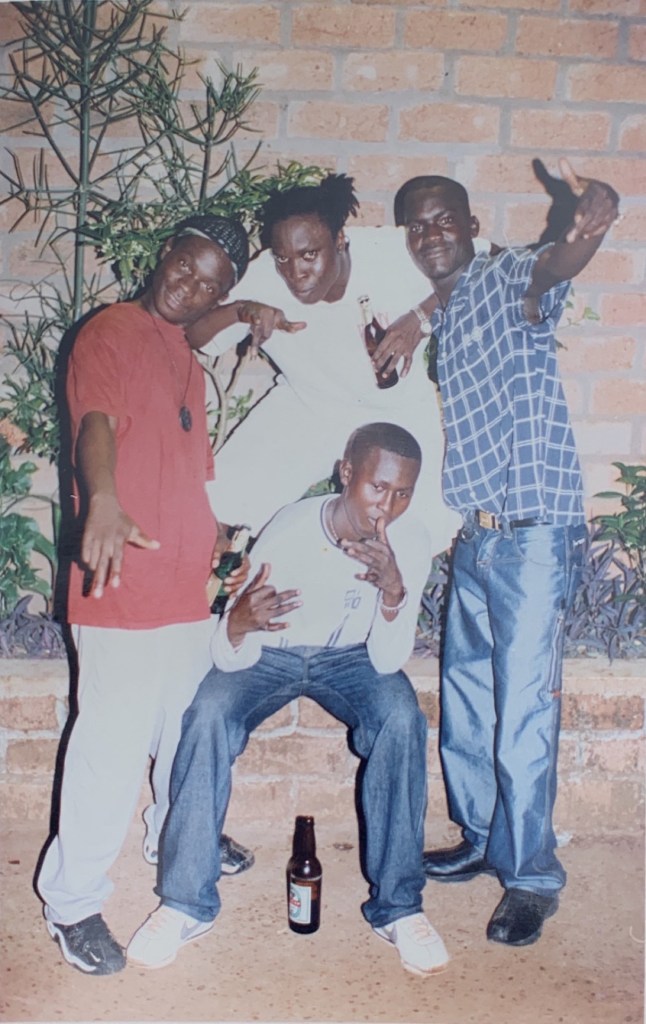

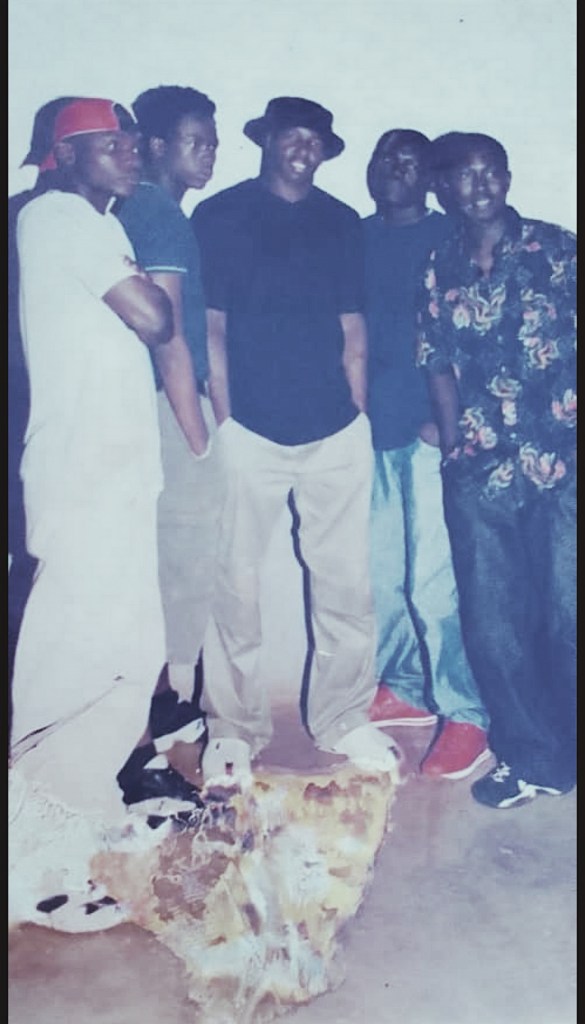

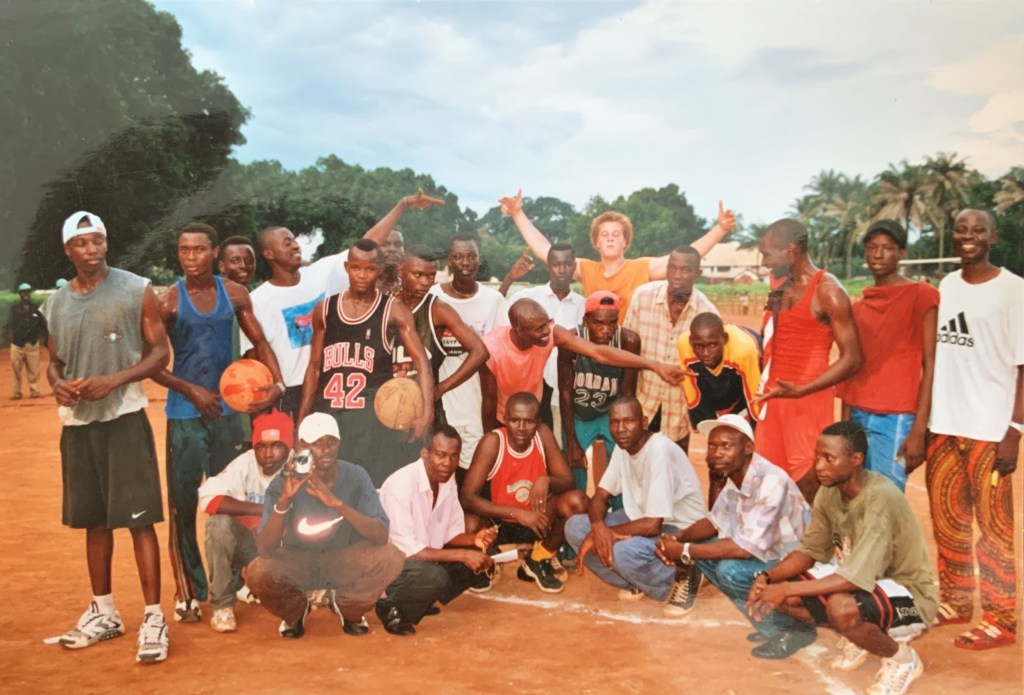

At the same time, in the late 1990s, in Bria, in the Central African Republic, music was already central to my life. With Gbekpa Crew, we were among the early voices of rap and hip-hop in the east of the country, particularly in the Haute-Kotto region. We often performed at the local bar-club Palace Kotto, dropping verses, moving as a group, dancing in choreography as much as rapping. It was raw, local, and alive.

That’s where rhythm became a way of speaking for me. Music wasn’t about survival. It was about belonging, storytelling, and staying connected as a group.

Coming from a fortunate family background in a deeply unequal environment, I carried an internal conflict early on. Music became a way to stay connected, to refuse separation, and to make sure no one around me was left behind. It was physical. It was social. It was necessary.

@ Palace Kotto

Those years produced the conditions that made Ancestral Soul inevitable.

By the time my first official electronic releases appeared in 2006, the foundations were already laid. The term Ancestral Soul did not describe something that existed independently of me. It named a language I was actively inventing through practice.

NAMING A GENRE

Ancestral Soul began as an intentional naming. I first used the term on a remix, Seed Allstar & Quentin Harris – Sniper (Boddhi Satva Ancestral Soul Remix), to clearly mark a sound I was shaping, one rooted in ancestry, emotion, and club culture, but not confined to any existing genre.

At first, there was no pushback. The sound felt fresh and fit comfortably on the edges of house music, where experimentation was still welcomed.

But the roots of that sound were already shaped by something deeper.

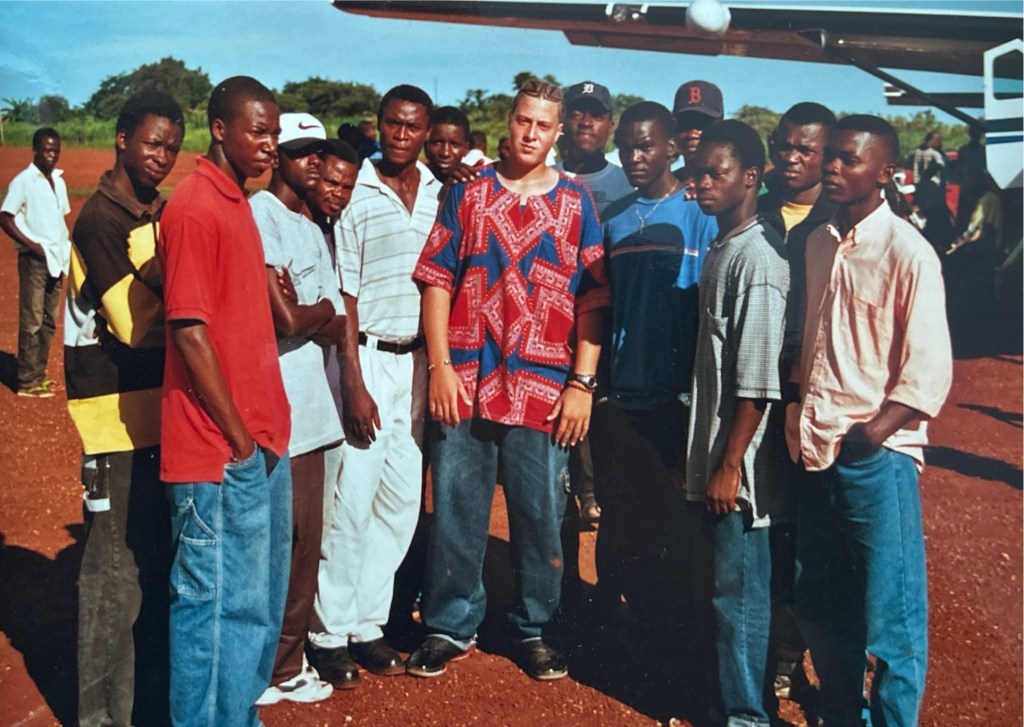

When my parents decided to send me out of the Central African Republic to complete my final year of high school, it created a rupture I wasn’t prepared for. I was 17, about to turn 18, and I had no intention of leaving. My life, my grounding, my people were there. Being forced to go wasn’t experienced as opportunity. It was separation.

(Bria, Central African Republic)

That displacement cut deep. It introduced a form of pain and struggle that had everything to do with identity, belonging, and continuity. Music became the only space where I could carry what had been interrupted. Where I could hold the country I left, the people I refused to abandon, and the self I was still forming.

Ancestral Soul took shape inside that tension.

Maybe as nostalgia, but surely as a way to maintain coherence while everything else was being pulled apart.

I created the term to name my own practice because no existing category could contain what I was building. Over time, as the work accumulated, audiences and collaborators began to recognise a consistent constellation of sonic and emotional traits.

Ancestral Soul became a genre not by following a template, but by staying consistent over time. It couldn’t be reduced to a style because it was never meant to do just one thing.

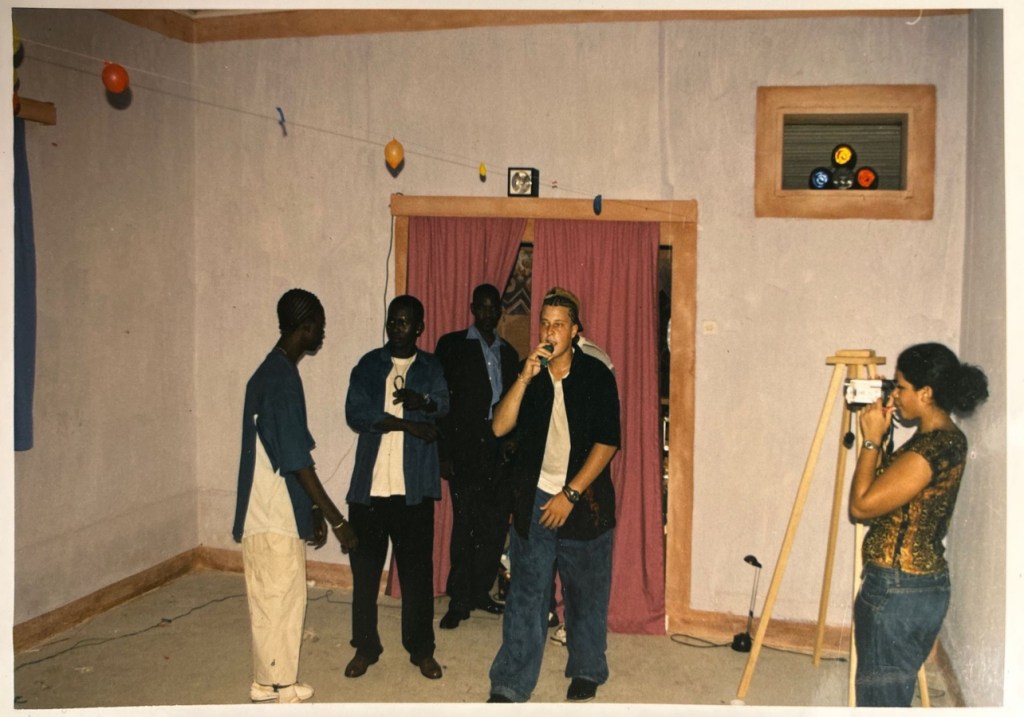

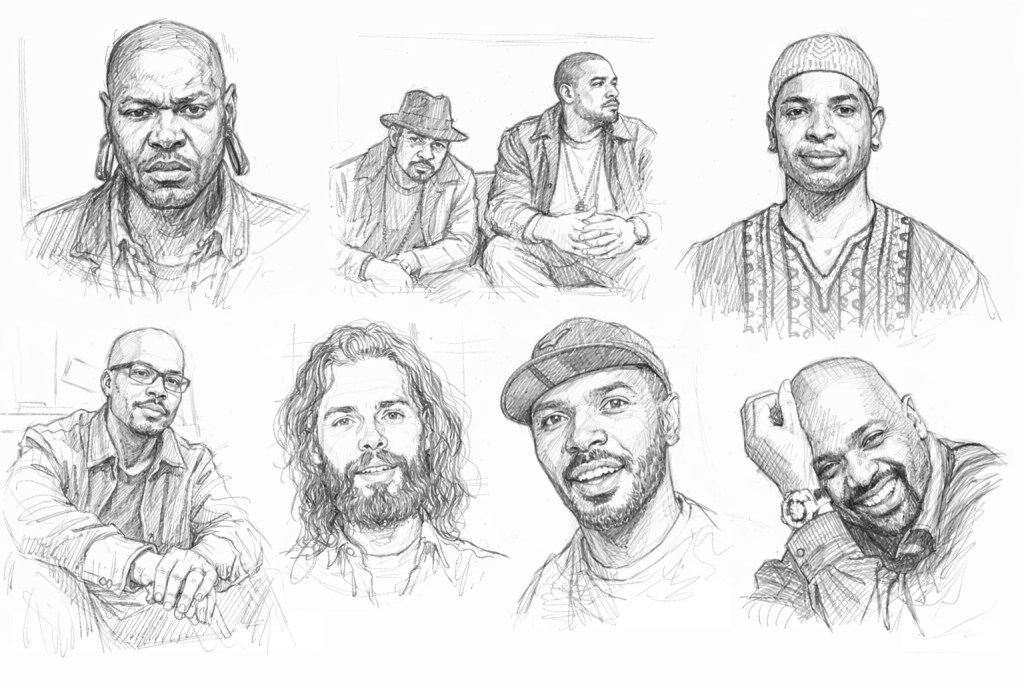

(WMC Miami 2005)

(WMC Miami 2005)

(Walvis Bar, Brussels)

That consistency was carried early on by people who recognised direction before there was recognition.

DJ Pippi, a legendary figure from Ibiza, was one of them. Alongside Alton Miller, he recognised early on that I wasn’t just passionate, but serious. He listened to my demos, understood the direction I was taking, and took the time to meet my parents so they could see the level of commitment and discipline required in this world. At a moment when the path was unfamiliar, his guidance helped frame it clearly and responsibly.

In 2005, Pippi invited me to the Winter Music Conference in Miami, which at the time was the place where the electronic music industry converged. I arrived with about fifty vinyl promos in my bag, nervous, barely speaking English, unsure how to approach anyone or navigate the politics of that world. Through Pippi and Alton, I met people like DJ Gregory and Pierre Ravan, who received my music with warmth and generosity. Those encounters mattered. They grounded me. They made the industry human.

That experience anchored something deeper. A sense of responsibility. Toward my parents, who had trusted me, and toward the path I had chosen. From that point on, there was no option to treat this lightly.

Much of what later became grouped under the name Afro House was already circulating through records, DJ sets, and dance floors at that time. Ancestral Soul was part of that groundwork. It helped open doors, expand palettes, and make space for African and diasporic expression inside electronic music before it became a category.

FROM LANGUAGE TO MOVEMENT

That pattern isn’t unique to my story. It’s how house music has always grown, from people building something together long before it was named or packaged.

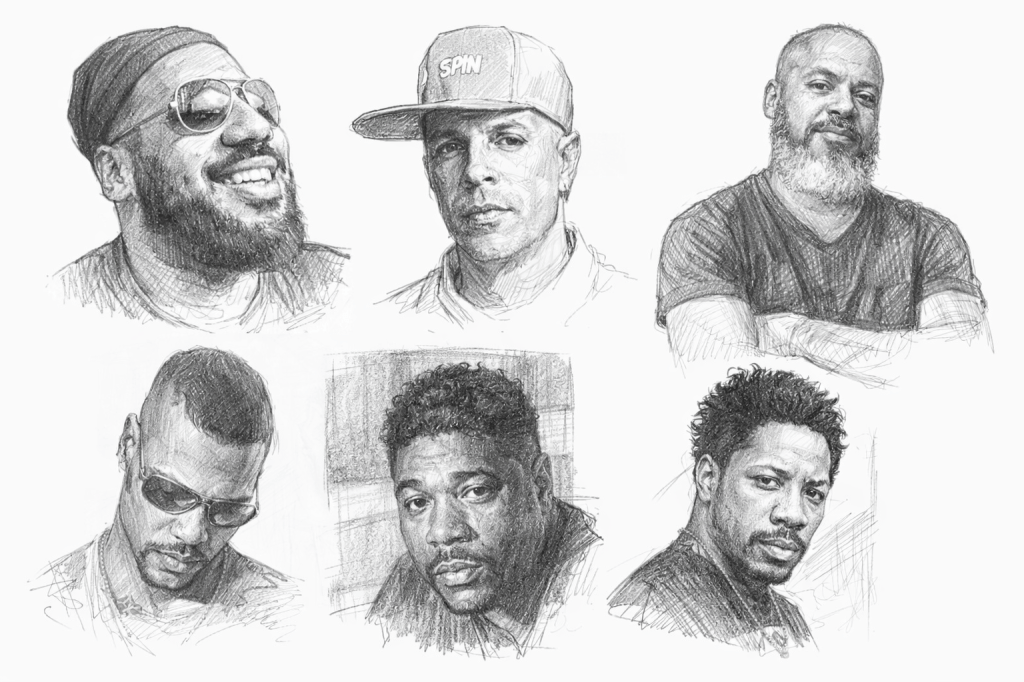

In Chicago, New York, New Jersey, Detroit, Baltimore, and beyond, DJs, producers, dancers, and entire communities turned records into rituals. Long before the industry learned how to package or label the culture, figures like Ron Hardy, Frankie Knuckles, Larry Levan, David Mancuso, Larry Heard, Timmy Regisford, Joe Claussell, Masters at Work, Osunlade, Ron Trent, Chez Damier, Quentin Harris, Alton Miller, Tony Touch, and Ian Friday, among many others, shaped spaces where sound, body, and spirit were inseparable.

But the culture didn’t live in the booth alone.

It lived on dance floors, through sound systems, and inside moving bodies. House dance, ballroom culture, and other underground club disciplines weren’t reactions to the music, they were part of what powered it. From the United States to France and Japan, dancers acted as real-time translators of sound. Figures such as Willi Ninja, Marjory, Voodoo Ray, Babson, and others, alongside living legends like Hiro, Shan S, and Archie Burnett, shaped how the music was inhabited, interpreted, and passed on.

DJs, in turn, operated as connectors as much as selectors. They kept ideas circulating freely between hip-hop, house, Latin freestyle, and wider dance cultures, maintaining spaces where sound, movement, and identity could mix instead of being separated into rigid scenes.

At its core, this ecosystem was rooted in Black, Latino, and queer communities, especially gay Black and Latino spaces, and deeply nourished by Caribbean and Afro-diasporic memory, spirituality, and ritual. House music here was never just entertainment. It was social glue, quiet resistance, and affirmation.

Within this living tradition, individual sounds growing into shared movements isn’t the exception, it’s the rule. Ancestral Soul evolved alongside Afro House, which had long existed before parts of it were simplified and repackaged by the industry, each carrying its own depth within the same cultural ecosystem.

WHAT THE SOUND CARRIES

Ancestral Soul is often reduced to the words “too deep”, “Too strange” or “too African.” Those words are attempts to simplify what refuses to be domesticated!

What they fail to grasp is everything the sound actually carries.

It carries love, not just romance, but devotion, longing, and distance. It carries loss, the kind that reshapes you quietly, and death, not as spectacle, but as continuity. It holds grief, elegance, defiance, and the tension of survival, while moving effortlessly through fashion, swagger, abstraction, politics, and spirit at the same time.

It can be bold and gentle within the same track.

Ceremonial and street-level.

Intimate and confrontational.

Sonically, Ancestral Soul moves freely. Through deep house and house, but also drum and bass, hip-hop, R&B, jungle, jazz, and polyphonic writing. Through ndombolo, soukouss, zouk, semba, coupé-décalé, gouyad, and the traditional and folkloric languages of the African continent. It absorbs techno, indie rock, new age, and other peripheral forms when they serve expression rather than posture.

SPEED, OUTPUT, SURVIVAL

In my opinion, one of the most persistent misunderstandings is that depth requires slowness.

My reality contradicts that idea.

I have always worked fast. Writing, composing, and producing music has never been a bottleneck for me. Long before the arrival of AI tools, I was already able to generate up to fifteen musical ideas or finished tracks per week (of course i took breaks from time to time).

Over time, my approach evolved alongside the industry itself. As physical formats gave way to digital ecosystems, conversations with peers, including Kaysha, helped sharpen my awareness of where music distribution and audience behaviour were heading. The shift toward frequency, accessibility, and continuity did not happen overnight, and neither did my adoption of it. Coming from an underground culture that valued rarity over volume, and supported by a strong period of DJ bookings, there was little initial urgency to think in terms of catalog density or long-term digital strategy.

That perspective changed gradually.

From 2016, and more clearly from 2018, I shifted into a steady, often weekly release rhythm.

At first, it was reactive. I started seeing doors close as the sound was increasingly framed as too deep, too African, or too Black.

The interest didn’t disappear, but the spaces willing to host it did. I didn’t dilute the music; I structured it, and that became the strategy.

This choice also mirrored broader industry shifts. Recent Spotify data has only confirmed what experience already proved: regular releases sustain listener attention, boost discoverability, and match the pace at which people now consume music. Dropping work every few months is no longer viable for anyone building enduring value.

For me, this frequency is not about chasing fleeting spikes. It stems from a deep love of creating and a sense of responsibility to longtime supporters and to future listeners alike. I am building catalogue, legacy, and lasting assets.

The same principle extends beyond recorded tracks. Growing Ancestral Soul has involved diversifying touchpoints: live mixes, podcasts, YouTube shows, and initiatives like the Quarantine Grooves sessions during the pandemic. These were never mere side projects; they were organic branches of the same ecosystem, opening new doors, strengthening connections, and keeping the music alive and circulating.

In an era where music risks becoming pure commodity, true sustainability arises from coherent volume, not hopeful scarcity. Speed, in this sense, is not the enemy of depth; it is the force that allows depth to gather, resonate, and endure.

LINEAGE AND RISK

A decisive phase in shaping my ear came through Alton Miller. Not just as a mentor, but as a big brother. We lived together as roommates in my apartment for nearly two years, sharing the same roof, the same days, the same silences. Music was part of everyday life, not a lesson plan. We listened, we talked, we argued, we sat with records. He taught me patience, restraint, and how to let emotion sit inside a track without forcing it. That transmission didn’t happen in studios or meetings. It happened at home.

Out of that closeness came my first official release, Alton Miller and Boddhi Satva – Prelude to a Motion EP, on ATAL Music. It mattered because it was rare. Established names don’t often put their reputation next to an unknown voice, especially not that early. Alton did, and that trust stayed with me.

Later, another risk shifted everything.

My 1st Album on Vega Records

My connection with Louie Vega came at a decisive moment. It was first facilitated by Mr. V, through our collaboration on V feat. Jill Scott – Born Again, which we remixed together. The record was released on BBE Music and licensed to Vega Records, offering an early and public validation of the musical language I was building.

It was Lou Gorbea, however, who truly pushed for a direct connection between Louie and me. From there, things moved quickly.

Louie didn’t just sign me. He invited me to record in New Jersey, opening together with his wife Anané and Nico their son the door to their home. The trust and love they placed in me shaped the work and set a standard I continue to honor.

That relationship also brought me into the Vega family ecosystem. I became part of the Get Together events, performing across Ibiza, Greece, New York, London, and beyond, placing the music inside a living lineage rather than at the margins.

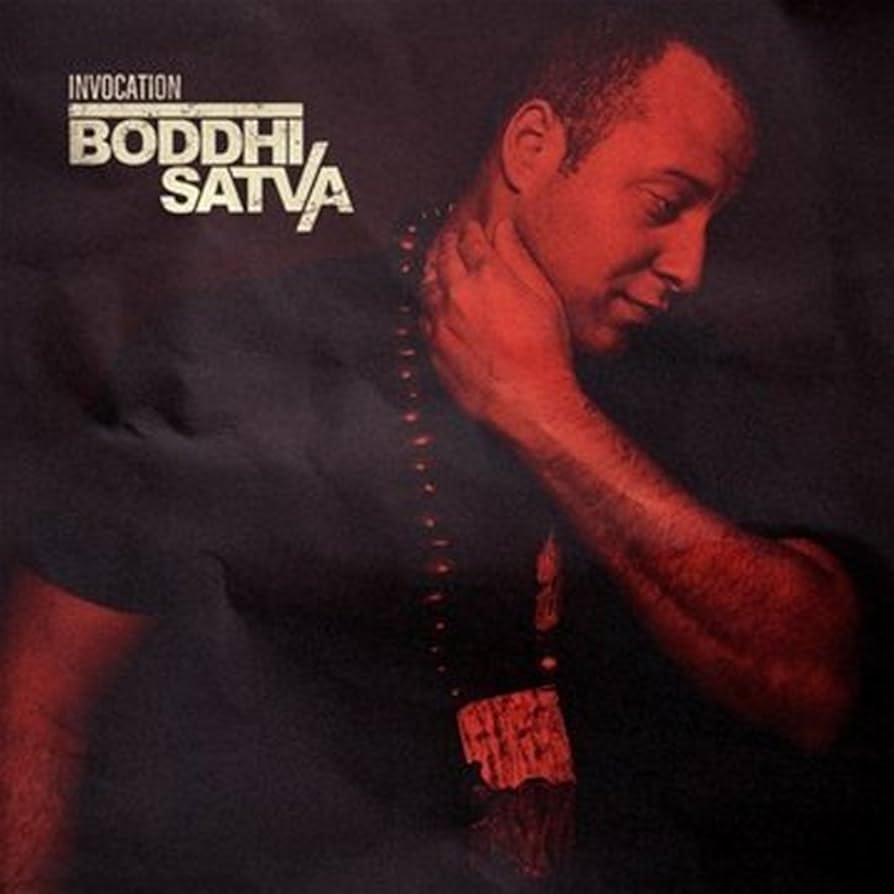

The journey formally began with Punch Koko, featuring Yacoub, followed by Stop Jealousy with Zé Pequenio, and ultimately my debut album Invocation on Vega Records. It was a unique alignment—one that demonstrated how mentorship from a figure like Louie Vega can profoundly change an artist’s trajectory, provided the artist is willing to meet that trust with discipline and work.

RECORDS THAT DEFINED THE SOUND

Ancestral Soul did not take shape through theory. It took shape through records.

Some were original compositions, others reinterpretations, remixes, or productions, but all were part of the same cultural movement.

The first marker was Prelude to a Motion, with Alton Miller, released on ATAL Music. Beyond being my first official release, it set the tone: patience, emotional restraint, and depth without excess. The project featured vocals by Okako and Sai Sai Mouss, both close friends, alongside saxophone solos by Sapuca Marcelo and bass by Humberto “Wuti” Gonzalez. It announced a way of listening.

That chapter was followed by See The Day, this time just Alton and myself, with Alton on vocals.

That language became fully legible with Bria’s Offering, released on Yoruba Records and later featured on Soul Heaven. The track resonated deeply in Southern Africa and beyond, often cited as a formative influence on Afro-centric house movements of the time. It established Ancestral Soul as a sound that could travel without being diluted.

Warriors of Africa, featuring Fredy Massamba, originally released on my label Offering Recordings was licensed to Shelter Records under the supervision of Freddy Sanon who comissioned a remarkable remix bylegendary Producer Sting International, confirmed the sound’s transatlantic weight. Around the same period, tracks such as

Gotta Get With You (Ancestral Mix) and The Thing About Deep placed Ancestral Soul firmly inside the lineage of New York and New Jersey house culture, while still sounding unmistakably its own.

With Punch Koko, followed closely by Ngnari Konon with Oumou Sangaré, the language took another step. Malian musical structures were not used as ornament, but as foundation. Ngnari Konon marked Oumou Sangaré’s first electronic collaboration at the time and demonstrated a core principle of Ancestral Soul: tradition does not need translation. It can lead.

As the language expanded, so did its emotional and cultural range. Records like Trouble Fête with Badi and Mama Kosa with Kaysha deepened its rhythmic and diasporic grounding, while My Heart with Nelson Freitas opened it toward a more intimate, melodic space. Collaborations such as Beautiful People with Les Nubians, Love Will with Bilal, Skin Diver with Teedra Moses, Benefit with Omar, Who Am I with Athenai & C. Robert Walker, Sweet Brown Sugar with E-Man, and Finesse Me with Raheem DeVaughn embedded Ancestral Soul within a broader Black Atlantic conversation, where soul, house, and lived experience met naturally.

Remixes and reinterpretations played an equally central role. Versions of Wilile (Mangala Camara), Ah Ndiyah (Oumou Sangaré), Crossroads (Tracy Chapman), and Thinkin About You (Frank Ocean) were not exercises in crossover, but acts of translation, extending Ancestral Soul into unexpected spaces while preserving its core intent.

Later works, including Kilulu from Manifestation, continued to refine the language. Taken together, these records form a catalog that speaks volume and a body of work that DJs, dancers, and listeners recognise not because of branding, but because of coherence over time.

OFFERING RECORDINGS

Those records defined the sound, but they also revealed its limits within existing systems. As Ancestral Soul expanded, it became clear that sustaining it would need more than releases alone.

As Ancestral Soul travelled (and still does) it was often reduced to being too Black, too African, too deep, too ancestral. These were never aesthetic critiques. They were signs of discomfort. A way of acknowledging that the sound resisted easy packaging, replication, or dilution. Offering Recordings became the structure that allowed that resistance to exist without apology.

Over the years, the label became a platform for launches, first records, and decisive moments in many artists’ careers. Often at times when few other structures were willing to take the risk. It was not driven by volume or trend cycles, but by alignment. The question was never whether a sound would sell quickly, but whether it would still make sense with time.

Offering did not remain confined to releases. It extended on air with Frequencies of Offering radio show into physical space through Offering Nights, A Night of Offering, and later the breakthrough ANCESTRAL nights, curated by Ivan Diaz and myself. We never conceived these events as showcases, but as environments. Spaces where Afro-centric cultures could exist boldly, without being reduced to a single narrative. Djoon was our first home, grounding the project before we took it across eleven countries. Through these events, we pioneered practices that later became more widely adopted, treating sound, movement, identity, and community as a single language. Africa was always present, in dialogue with the diaspora, electronic music, jazz, house, and everything else that belonged in the room.

The dancer community was essential to that evolution. Paradox-Sal, an all-female collective formed and directed by our late brother Babson, gave the project a physical intelligence that went beyond performance. Alongside them, the Serial Stepperz helped carry the energy and codes of the nights. Since 2017, ANCESTRAL has been fully run by Ivan Diaz, who ensures its continuity and evolution.

Those nights proved decisive. They paved the way for a broader, more confident embrace of Afro-centric expression in club culture, while remaining open and hybrid by design. They showed that depth and accessibility were not opposites, and that cultural specificity did not require isolation.

As the label evolved, different energies helped it breathe and expand. Ivan Diaz, and later Yves Sifa, played key roles in giving Offering new momentum and direction during important phases of its life. Each period brought movement, experimentation, and growth. The label was never static, and it was never meant to be.

Offering also grew through the commitment and belief of close collaborators and supporters. The French Twins, WF Rani G, Dimitris Katsikinis, among many others, contributed materially, artistically, and structurally to what the label became. Their involvement was not incidental. It was part of a shared understanding that this work required patience, trust, and long-term thinking.

Eventually, I stepped back into full leadership. Not to undo what had been built, but to recenter the project. The focus returned clearly to my productions and Boddhi Satva–related works, while preserving Offering Recordings as what it was always intended to be: a long-term cultural tool, not a trend-driven vehicle.

Offering endures because it was never engineered to chase relevance. It was built to support work that needed time, context, and care. In that sense, the label did not simply accompany Ancestral Soul. It made its continued existence possible.

WHAT ENDURES

Not everything is meant to be resolved.

Some work is designed to stay in motion, changing shape as it passes through people, places, and time. What matters is not how loudly it announces itself, but how consistently it holds.

Ancestral Soul was never built to dominate a moment. It was built to survive many of them. To return when the noise fades. To remain intelligible long after trends have moved on.

What endures is not visibility, but coherence.

Not speed, but alignment.

Not consensus, but listening.

The sound holds memory and future in the same breath. Intimacy and resistance in the same groove. It asks for attention, not approval. And it rewards patience more than immediacy.

If you’ve read this far, thank you for the time and the listening. What follows won’t need explanation.

Time will take care of that.

Boddhi Satva

Creator of Ancestral Soul

Founder of Offering Recordings